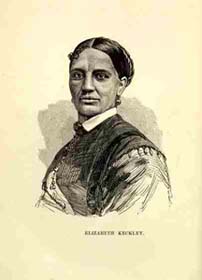

Elizabeth Keckly

A Brief Biography

Elizabeth Keckly* was a remarkable woman who was born into slavery in 1818 just south of the major market center of Petersburg, Virginia. She learned her craft—sewing—from her mother, who was an expert seamstress enslaved in the Burwell family. When Reverend Burwell, Keckly's master and half-brother (they shared a father) relocated to Hillsborough, North Carolina, in 1832, she soon followed. Six years later, Anna Burwell, Keckly's mistress, started a school for young girls in the family home, with an already over-worked Keckly charged as the sole servant. In the Burwell household, Keckly was subject to physical and sexual abuse. She gave birth to her only child, a son, as a result of being molested by a white acquaintance of the Burwells.

After thirty years of enslavement in the Burwell family, Keckly procured enough saved income from portions of "self-hired" earnings and loans from her white female customers to buy herself and her son out of slavery. Later, Keckly moved to Washington, DC and became the sole proprietor of one of the most exclusive dressmaking shops in the city, where she employed other seamstresses. She drew her female clients from the capitol's elite, and ultimately the executive office, becoming the personal seamstress and confidante of the first lady, Mary Todd Lincoln. Much of Keckly's enduring fame results from her relationship with the first lady, which is documented in Behind the Scenes, or Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House, the first tell-all expose of the private life of a president and his family. Keckly's memoir recounts her experiences as a talented and enterprising artisan and her ultimate achievement of political and economic independence.

In addition to providing a rich portrait of a black woman who operated a successful business in slavery and freedom, Keckly's life also provides a rare opportunity to examine the significance of the needle arts. From the colonial era through the mid-nineteenth century, when the needle arts became more mechanized and standardized, skilled dressmaking continued to be a very specialized, prestigious, and competitive activity for both white and black women. Indeed because women's clothing required a large amount of fabric and was so complex to construct, the mechanization of women's garment construction came much later than for men's clothing.

Keckly's success was part business savvy, part technical skills, and part fashion design talent fueled by a driving ambition. She had an exceptional ability to combine the latest European patterns with her own styles in catering to the tastes of her clients. This blending of Old World traditions with indigenous styles and the artist’s personal aesthetics helps define American culture as a whole.

*Elizabeth Keckly's last name is often spelled "Keckley." We are honoring Keckly's own spelling of her last name, which lacked the extra "e." Although we encourage the use of "Keckly," some of the materials that you will reference for lesson plans on the Crafting Freedom website will present the name with the extra "e."